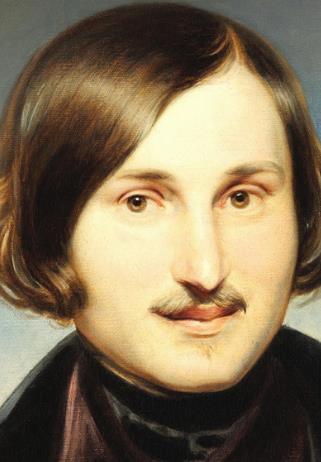

GOGOL, Nicolai

The Overcoat

…..

And Petersburg was left without Akakii Akakievich, as though he had never lived there. A being disappeared, and was hidden, who was protected by none, dear to none, interesting to none, who never even attracted to himself the attention of an observer of nature, who omits no opportunity of thrusting a pin through a common fly, and examining it under the microscope...

…..

The Tale of How Ivan Ivanovich Quarreled with Ivan Nikiforovich

The whole group represented a powerful picture: Ivan Nikiforovich standing in the middle of the room in all his unadorned beauty! The woman, her mouth gaping and with a most senseless and fearful look on her face! Ivan Ivanovich with one arm raised aloft, the way Roman tribunes are portrayed! This was an extraordinary moment! A magnificent spectacle! And yet there was only one spectator: this was the boy in the boundless frock coat, who stood quite calmly and cleaned his nose with his finger.

…..

“Excuse me, Ivan Ivanovitch; my gun is a choice thing, a most curious thing; and besides, it is a very agreeable decoration in a room.”

“You go on like a fool about that gun of yours, Ivan Nikiforovitch,” said Ivan Ivanovitch with vexation; for he was beginning to be really angry.

“And you, Ivan Ivanovitch, are a regular goose!”

If Ivan Nikiforovitch had not uttered that word they would not have quarrelled, but would have parted friends as usual; but now things took quite another turn. Ivan Ivanovitch flew into a rage.

…..

The Inspector-General

…..

GOVERNOR

And then I must call your attention to the history teacher. He has a lot of learning in his head and a store of facts. That's evident. But he lectures with such ardor that he quite forgets himself. Once I listened to him. As long as he was talking about the Assyrians and Babylonians, it was not so bad. But when he reached Alexander of Macedon, I can't describe what came over him. Upon my word, I thought a fire had broken out. He jumped down from the platform, picked up a chair and dashed it to the floor. Alexander of Macedon was a hero, it is true. But that's no reason for breaking chairs. The state must bear the cost.

…..

What are you laughing at? You are laughing at yourself.

…..

Dead Souls

…..

Chichikov’s amusement at the peasant’s outburst prevented him from noticing that he had reached the centre of a large and populous village; but, presently, a violent jolt aroused him to the fact that he was driving over wooden pavements of a kind compared with which the cobblestones of the town had been as nothing. Like the keys of a piano, the planks kept rising and falling, and unguarded passage over them entailed either a bump on the back of the neck or a bruise on the forehead or a bite on the tip of one’s tongue. At the same time Chichikov noticed a look of decay about the buildings of the village. The beams of the huts had grown dark with age, many of their roofs were riddled with holes, others had but a tile of the roof remaining, and yet others were reduced to the rib-like framework of the same. It would seem as though the inhabitants themselves had removed the laths and traverses, on the very natural plea that the huts were no protection against the rain, and therefore, since the latter entered in bucketfuls, there was no particular object to be gained by sitting in such huts when all the time there was the tavern and the highroad and other places to resort to.

Suddenly a woman appeared from an outbuilding—apparently the housekeeper of the mansion, but so roughly and dirtily dressed as almost to seem indistinguishable from a man. Chichikov inquired for the master of the place.

“He is not at home,” she replied, almost before her interlocutor had had time to finish. Then she added: “What do you want with him?”

“I have some business to do,” said Chichikov.

“Then pray walk into the house,” the woman advised. Then she turned upon him a back that was smeared with flour and had a long slit in the lower portion of its covering. Entering a large, dark hall which reeked like a tomb, he passed into an equally dark parlour that was lighted only by such rays as contrived to filter through a crack under the door. When Chichikov opened the door in question, the spectacle of the untidiness within struck him almost with amazement. It would seem that the floor was never washed, and that the room was used as a receptacle for every conceivable kind of furniture. On a table stood a ragged chair, with, beside it, a clock minus a pendulum and covered all over with cobwebs. Against a wall leant a cupboard, full of old silver, glassware, and china. On a writing table, inlaid with mother-of-pearl which, in places, had broken away and left behind it a number of yellow grooves (stuffed with putty), lay a pile of finely written manuscript, an overturned marble press (turning green), an ancient book in a leather cover with red edges, a lemon dried and shrunken to the dimensions of a hazelnut, the broken arm of a chair, a tumbler containing the dregs of some liquid and three flies (the whole covered over with a sheet of notepaper), a pile of rags, two ink-encrusted pens, and a yellow toothpick with which the master of the house had picked his teeth (apparently) at least before the coming of the French to Moscow. As for the walls, they were hung with a medley of pictures. Among the latter was a long engraving of a battle scene, wherein soldiers in three-cornered hats were brandishing huge drums and slender lances. It lacked a glass, and was set in a frame ornamented with bronze fretwork and bronze corner rings. Beside it hung a huge, grimy oil painting representative of some flowers and fruit, half a water melon, a boar’s head, and the pendent form of a dead wild duck. Attached to the ceiling there was a chandelier in a holland covering—the covering so dusty as closely to resemble a huge cocoon enclosing a caterpillar. Lastly, in one corner of the room lay a pile of articles which had evidently been adjudged unworthy of a place on the table. Yet what the pile consisted of it would have been difficult to say, seeing that the dust on the same was so thick that any hand which touched it would have at once resembled a glove. Prominently protruding from the pile was the shaft of a wooden spade and the antiquated sole of a shoe. Never would one have supposed that a living creature had tenanted the room, were it not that the presence of such a creature was betrayed by the spectacle of an old nightcap resting on the table.

Whilst Chichikov was gazing at this extraordinary mess, a side door opened and there entered the housekeeper who had met him near the outbuildings. But now Chichikov perceived this person to be a man rather than a woman, since a female housekeeper would have had no beard to shave, whereas the chin of the newcomer, with the lower portion of his cheeks, strongly resembled the curry-comb which is used for grooming horses. Chichikov assumed a questioning air, and waited to hear what the housekeeper might have to say. The housekeeper did the same. At length, surprised at the misunderstanding, Chichikov decided to ask the first question.

“Is the master at home?” he inquired.

“Yes,” replied the person addressed.

“Then were is he?” continued Chichikov.

“Are you blind, my good sir?” retorted the other. “I am the master.”

Involuntarily our hero started and stared. During his travels it had befallen him to meet various types of men—some of them, it may be, types which you and I have never encountered; but even to Chichikov this particular species was new. In the old man’s face there was nothing very special—it was much like the wizened face of many another dotard, save that the chin was so greatly projected that whenever he spoke he was forced to wipe it with a handkerchief to avoid dribbling, and that his small eyes were not yet grown dull, but twinkled under their overhanging brows like the eyes of mice when, with attentive ears and sensitive whiskers, they snuff the air and peer forth from their holes to see whether a cat or a boy may not be in the vicinity. No, the most noticeable feature about the man was his clothes. In no way could it have been guessed of what his coat was made, for both its sleeves and its skirts were so ragged and filthy as to defy description, while instead of two posterior tails, there dangled four of those appendages, with, projecting from them, a torn newspaper. Also, around his neck there was wrapped something which might have been a stocking, a garter, or a stomacher, but was certainly not a tie. In short, had Chichikov chanced to encounter him at a church door, he would have bestowed upon him a copper or two (for, to do our hero justice, he had a sympathetic heart and never refrained from presenting a beggar with alms), but in the present case there was standing before him, not a mendicant, but a landowner—and a landowner possessed of fully a thousand serfs, the superior of all his neighbours in wealth of flour and grain, and the owner of storehouses, and so forth, that were crammed with homespun cloth and linen, tanned and undressed sheepskins, dried fish, and every conceivable species of produce. Nevertheless, such a phenomenon is rare in Russia, where the tendency is rather to prodigality than to parsimony.

For several minutes Plushkin stood mute, while Chichikov remained so dazed with the appearance of the host and everything else in the room, that he too, could not begin a conversation, but stood wondering how best to find words in which to explain the object of his visit. For a while he thought of expressing himself to the effect that, having heard so much of his host’s benevolence and other rare qualities of spirit, he had considered it his duty to come and pay a tribute of respect; but presently even HE came to the conclusion that this would be overdoing the thing, and, after another glance round the room, decided that the phrase “benevolence and other rare qualities of spirit” might to advantage give place to “economy and genius for method.” Accordingly, the speech mentally composed, he said aloud that, having heard of Plushkin’s talents for thrifty and systematic management, he had considered himself bound to make the acquaintance of his host, and to present him with his personal compliments (I need hardly say that Chichikov could easily have alleged a better reason, had any better one happened, at the moment, to have come into his head).

With toothless gums Plushkin murmured something in reply, but nothing is known as to its precise terms beyond that it included a statement that the devil was at liberty to fly away with Chichikov’s sentiments. However, the laws of Russian hospitality do not permit even of a miser infringing their rules; wherefore Plushkin added to the foregoing a more civil invitation to be seated.

“It is long since I last received a visitor,” he went on. “Also, I feel bound to say that I can see little good in their coming. Once introduce the abominable custom of folk paying calls, and forthwith there will ensue such ruin to the management of estates that landowners will be forced to feed their horses on hay. Not for a long, long time have I eaten a meal away from home—although my own kitchen is a poor one, and has its chimney in such a state that, were it to become overheated, it would instantly catch fire.”

Translation by D. J. Hogarth

…..

Like the gigantic rampart of some endless fortress, with angle towers and embrasures, the hill heights ran their winding way for a thousand versts and more. Majestically they soared above the endless stretches of plains, now in escarpments, sheer walls of lime and clay fretted by gullies and cavities, now in gracefully rounded green swellings cloaked in lambskin like young brushwood springing from the felled trees, now, finally in dark thickets of woodland, so far spared the axe by some miracle. A river, true to its banks, now followed them in turns and twists, now left them for the meadows, then, bending itself into several bends, flashed fire like in the sun, hid itself in groves of birch, aspen and alder, and ran forth from them in triumph, attended by bridges, mills and weirs, which seemed to chase after it at every turn.

…..

Translation: David Magarshack